“It’s been a pretty crazy journey getting to the point that we’re at now,” says Deafheaven vocalist George Clarke. “And now we’re really in the eye of the storm, and it's… interesting.”

Less than three years ago, Clarke and Deafheaven guitarist Kerry McCoy were scratching out an impoverished existence in San Francisco’s Mission District, where they lived on food stamps and shared a tiny apartment with six other roommates. Deafheaven’s debut album, 2011’s Roads to Judah, had garnered some critical acclaim for its boundary-pushing blend of black metal, shoegaze and post-rock; but a rough year on the road supporting the record had left Clarke and McCoy destitute, and caused the other three members of the band to jump ship.

Rather than pack it in themselves, Clarke and McCoy found some new accomplices (drummer Dan Tracy, bassist Stephen Lee Clark, and guitarist Shiv Mehra) and poured their hopes and frustrations into Sunbather, an album that changed everything for them. The record not only was “the best-reviewed major album of 2013,” according to Metacritic, due to its many accolades — which included the top spot on Rolling Stone’s 20 Best Metal Albums of the year list — but also unexpectedly resulted in sold-out club dates and choice slots at festivals in the U.S., Europe, Australia and Asia.

The success of Sunbather enabled Clarke and McCoy to move to Los Angeles — “In San Francisco, we kind of realized we were paying more money to have less fun,” McCoy laughs — and enjoy a more somewhat more comfortable standard of living. But it also meant that the band had to get cracking on the next album shortly after wrapping up their final Sunbather dates.

“We’d been touring for a year and a half,” McCoy explains. “I literally only had like one or two new songs sketched out, and we had like four or five months to get this record written and into the studio. We’ve just got done releasing the biggest record of our lives, which took me a year and a half to write; and now I’m writing the follow-up to that in a third of the time, knowing that it’s going to get, like, four times the attention. That’s a lot of pressure,” he laughs.

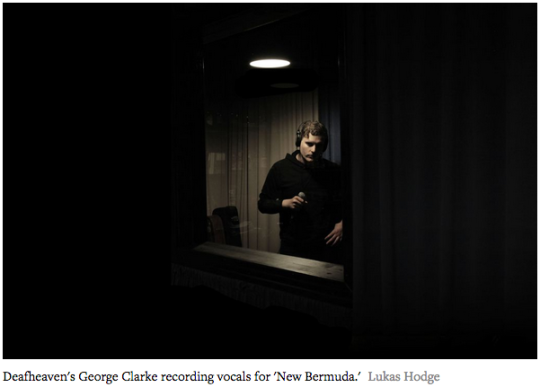

Under the gun to craft a follow-up to Sunbather, Deafheaven spent much of this spring holed up in rehearsals, before heading to Palo Alto’s Atomic Garden Recording and 25th Street Recording in Oakland to lay down tracks with producer Jack Shirley, who’d also been behind the boards for their previous two albums. “We did our last two records at Atomic Garden,” says Clarke, “but 25th Street has a really large drum room. We wanted to focus more on drum production for this record, so Jack suggested that we do all the drum tracks there.” “There was a lot of second-guessing because of the time crunch,” adds McCoy. “It was like, ‘Am I actually happy with this part? Or do I just want to be done writing for the day? Does this really work, or are we actually rushing through this?’”

Despite — or perhaps because of — the stress of the looming deadlines, the recording sessions resulted in New Bermuda, a stunning, five-track edifice of thundering sound that takes the expansive sonic attack of Sunbather to a darker, more metallic place, while also working some unexpected classic rock touches into the mix.

“That mixture of influences has kind of always been our thing, much to some peoples’ annoyance,” laughs McCoy. “But a lot of this record is us being like, 'Look, we are a metal band. We do a lot of other stuff, but we can solo; we can have some Slayer riffs in there. There was a lot of, 'Hey, what if we throw some traditional thrash metal stuff in here, but just make it our own?’ And I think it worked really well.”

McCoy, who writes Deafheaven’s music, cites Morbid Angel and Kill 'Em All–era Metallica as some of the main musical influences behind New Bermuda. But there are also moments throughout the album — like the gorgeous piano outro of the opening epic “Brought to the Water” or the Michael Schenker–esque wah-wah solo break on “Baby Blue” — that are clearly rooted in classic and/or alternative rock.

“I was definitely trying to distance myself from the whole shoegaze thing and go more towards alternative rock,” he says, “which is why there’s the Oasis homage at the end of 'Gifts for the Earth,’ and some of the songs have more of a slow-core vibe — like, my take on Low or Red House Painters. There’s even like a Wilco slide guitar-y thing on 'Come Back.’ Not so much reverb and spacey-ness, which in my opinion is being beaten to death currently, but more of an emphasis on hooks, riffs and real melodies.”

Though Clarke says that his lyrics aren’t directly influenced by McCoy’s music, his words mesh perfectly with the sense of tension and urgency imparted by the band on New Bermuda. The bleakness of his current lyrical perspective, he explains, stems from the realization that, after dreaming of success and stability for years, he’d actually created new stresses and anxieties for himself by achieving those things.

“Whereas Sunbather sort of had this hopeful, dreamlike feeling to it, New Bermuda is definitely more steeped in reality,” he says. “It has more to do with the idea of facing yourself, questioning what it was that you wanted in the first place, and dealing with complacency…

”'New Bermuda’ is the destination that you’re getting towards,“ he continues. "It’s basically sort of a play on the [Bermuda] Triangle — it’s like, you’re traveling to this place, and you think this is what you want, and you think this is where everything is going to be good. And before that happens, you’re swallowed up by the realities of life, the day-to-day.”

Still, Clarke insists, he’s far from displeased with Deafheaven’s graduation to bigger stages and larger audiences. “One thing that I don’t want to get misconstrued is the notion of my constant unhappiness,” he says. “I feel incredibly fortunate to be in the position that we’re in. I feel like we have worked incredibly hard, but we’ve also been lucky, and I really appreciate that. It’s just that, sometimes, I feel… It’s hard to explain, but it’s a sort of trapped feeling. And it’s also like, we’re in the middle of our career, and I’m afraid to lose it — and afraid of what comes next.”